Right now, we are especially interested in any information on the location/ownership of the three paintings shown below. If you know anything about them, please send your information to info@kershisnik.com.

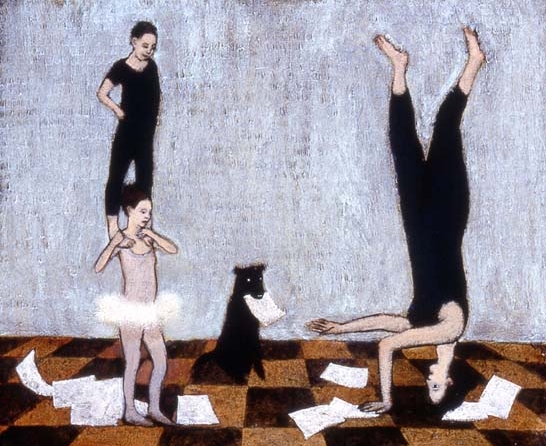

a thousand times we never knew the danger, 40x28 inches

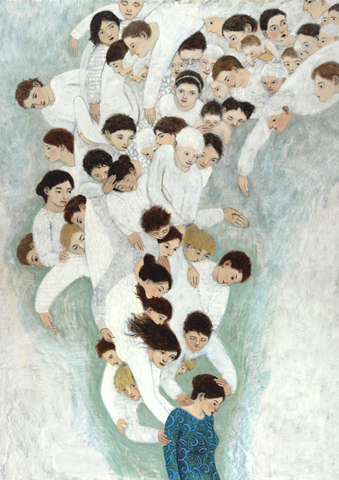

finding my way home, 12x12 inches

winter dancing, 9x12 inches

Below is an email communication we sent out to all those registered on our website regarding a Retrospective exhibit of Brian’s work coming up in 2024. In preparation for this exhibit, we are collecting as much information as we can about ownership of Brian’s original paintings. If you have any information about the location/ownership of any of Brian’s paintings we would welcome your input. Again anything you send to us should be send to info@kershisnik.com. Here is the original email which explains our project:

Dear Friends,

We would like to express our deep appreciation to all who responded to our previous letter requesting photos of original Kershisnik paintings. We were able to add a lot of valuable information to our database. If you responded to our first email, there is no need to respond again unless you have added new paintings to your collection.

This email is a follow up to encourage any of you who didn’t respond last time but had intended to, or if you have acquired any artwork since then. Again, we will greatly appreciate your assistance and hope you can take the time to send your photos and information. Brian is working on an editioned relief print (signed and numbered) that will be sent as a thank you to all those who have provided this critical information for our exhibition.

Here is the original email with an explanation of what we are doing and why:

The Museum of Art at BYU in Provo, Utah, has scheduled an extensive one-man show of my work in 2024. This is a great opportunity for me, but it is a fairly massive project to identify and locate the work that the curators would like to include. I have maintained an extensive archive of most of my work, but my records of the current locations of these works are not as complete. So, I am requesting your assistance. To those of you who have collected any of my original paintings and are willing to share the following information, I ask that you please send me handheld digital photos (including a detail shot of the title, if possible) of the pieces in your possession with the owner’s name, address, optional phone number and source of acquisition (source gallery). Do not reply to this email, but please send your information to info@kershisnik.com. I will add this information to my Index, but please know this information is not accessed publicly.

For this upcoming exhibit, or any future such exhibits, you may be contacted by me or my estate to ascertain your willingness to lend pieces from your collection. If you are willing to consider it at that time, your contact information will be shared, with your permission, with the exhibiting institution. I would recommend you consider such loans as long as the terms and protections offered meet your approval. Sending the photos and contact info to me by no means obligates you to any loan whatsoever. It helps me keep accurate provenance records. I only suggest that considering lending artwork to such exhibits is good for both of us in establishing history and provenance for pieces in your collection. You are free to require collector’s anonymity in the painting labels at such exhibitions if you wish.

Thank you for your assistance in this effort. If you have any questions before sending the information, please let me know.

Cheers, brian